These promotions will be applied to this item:

Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions.

Audiobook Price: $18.90$18.90

Save: $5.91$5.91 (31%)

- Highlight, take notes, and search in the book

- In this edition, page numbers are just like the physical edition

Your Memberships & Subscriptions

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required.

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Audible sample

Audible sample Follow the authors

OK

The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic Kindle Edition

Long before the American Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, a motley crew of sailors, slaves, pirates, laborers, market women, and indentured servants had ideas about freedom and equality that would forever change history. The Many Headed-Hydra recounts their stories in a sweeping history of the role of the dispossessed in the making of the modern world.

When an unprecedented expansion of trade and colonization in the early seventeenth century launched the first global economy, a vast, diverse, and landless workforce was born. These workers crossed national, ethnic, and racial boundaries, as they circulated around the Atlantic world on trade ships and slave ships, from England to Virginia, from Africa to Barbados, and from the Americas back to Europe.

Marshaling an impressive range of original research from archives in the Americas and Europe, the authors show how ordinary working people led dozens of rebellions on both sides of the North Atlantic. The rulers of the day called the multiethnic rebels a 'hydra' and brutally suppressed their risings, yet some of their ideas fueled the age of revolution. Others, hidden from history and recovered here, have much to teach us about our common humanity.

- ISBN-13978-0807050156

- PublisherBeacon Press

- Publication dateSeptember 3, 2013

- LanguageEnglish

- File size14.1 MB

Kindle E-Readers

- Kindle Paperwhite (5th Generation)

- Kindle Scribe, 1st generation (2024 release)

- Kindle Voyage

- All New Kindle E-reader

- Kindle Paperwhite (11th Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite

- Kindle Oasis (9th Generation)

- All New Kindle E-reader (11th Generation)

- Kindle Touch

- All new Kindle paperwhite

- Kindle Paperwhite (10th Generation)

- Kindle Paperwhite (12th Generation)

- Kindle

- Kindle Oasis

- Kindle Oasis (10th Generation)

- Kindle Scribe (1st Generation)

- Kindle (10th Generation)

Fire Tablets

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

Amazon.com Review

Arguing that this history of resistance to globalism has been unjustly overlooked, Linebaugh and Rediker delineate key episodes. When, for instance, a group of English sailors and common laborers were shipwrecked on the island of Bermuda en route to America, they created their own communal government, which was so pleasant to them that they refused to be "rescued" and had to be removed to the colonies by force. Their ideological descendants later banded with runaway slaves and other discontents to form multi-ethnic, multilingual pirate navies that hindered the transatlantic traffic in metals, jewels, and captive humans. Some of the men and women involved in these pirate bands, this "Atlantic proletariat," put their skills at the service of the American Revolution, which, in the author's view, "ended in reaction as the Founding Fathers used race, nation, and citizenship to discipline, divide, and exclude the very sailors and slaves who had initiated and propelled the revolutionary movement." The fire of rebellion soon spread all the same, they note, to such places as Haiti, Ireland, France, even England, helped along by these peripatetic and unsung rebels.

Linebaugh and Rediker's book is provocative and often brilliant, opening windows onto little-known episodes in world history. --Gregory McNamee

From Publishers Weekly

Copyright 2000 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Review

"A landmark in the development of an Atlantic perspective on early American history. Ranging from Europe to Africa to the Caribbean and North America, it makes us think in new ways about the role of working people in the making of the modern world."--Eric Foner, author of The Story of American Freedom

"What would the world look like had the levelers, the diggers, the ranters, the slaves, the castaways, the Maroons, the Gypsies, the Indians, the Amazons, the Anabaptists, the pirates . . . won? Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker show us what could have been by exhuming the revolutionary dreams and rebellious actions of the first modern proletariat, whose stories~until now~were lost at sea. They have recovered a sunken treasure chest of history and historical possibility and spun these lost gems into a swashbuckling narrative full of labor, love, imagination, and startling beauty." --Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Yo' Mama's Disfunktional!

"The Many-Headed Hydra is about connections others have denied, ignored, or underemployed. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Europe, Africa, and the Americas came together to create a new economy and a new class of working people. Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker tell their story with deep sympathy and profound insight. . . . A work of restoration and celebration of a world too long hidden from view."--Ira Berlin, author of Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America

"More than just a vivid illustration of the gains involved in thinking beyond the boundaries between nation-states. Here, in incendiary form, are essential elements for a people's history of our dynamic, transcultural present."--Paul Gilroy, author of The Black Atlantic

"This is a marvelous book. Linebaugh and Rediker have done an extraordinary job of research into buried episodes and forgotten writings to recapture, with eloquence and literary flair, the lost history of resistance to capitalist conquest on both sides of the Atlantic."--Howard Zinn, author of A People's History of the United States

About the Author

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

From the Introduction

With Rachel Carson, let us first look from above: “The permanent currents of the ocean are, in a way, the most majestic of her phenomena. Reflecting upon them, our minds are at once taken out from the earth so that we can regard, as from another planet, the spinning of the globe, the winds that deeply trouble its surface or gently encompass it, and the influence of the sun and moon. For all these cosmic forces are closely linked with the great currents of the ocean, earning for them the adjective I like best of all those applied to them—the planetary currents.” The planetary currents of the North Atlantic are circular. Europeans pass by Africa to the Caribbean and then to North America. The Gulf Stream then at three knots moves north to the Labrador and Arctic currents, which move eastward, as the North Atlantic Drift, to temper the climates of northwestern Europe.

At Land’s End, the westward foot of England, break waves whose origins lie off the stormy coast of Newfoundland. Some of these breakers may even be traced to the coast of Florida and the West Indies. For centuries fishermen on the lonely shores of Ireland have been able to interpret these long Atlantic swells. The power of an ocean wave is directly related to the speed and duration of the wind that sets it in motion, and to the “length of its fetch,” or the distance from its point of origin. The longer the fetch, the greater the wave. Nothing can stop these long waves. They become visible only at the end, when they rise and break; for most of their fetch the surface of the ocean is undisturbed. In 1769, Postmaster General Benjamin Franklin noted that packets from Falmouth took about two weeks longer to reach New York than merchant ships took to sail from Rhode Island to London. In talking to Nantucket whalers, he learned about the Gulf Stream: the fishermen and the whales kept out of it, while the English captains stemmed the current, “too wise to be counselled by simple American fishermen.” He drew up some “Maritime Observations” in 1786, and with these the chart of the Gulf Stream was published in America.

The circular transmission of human experience from Europe to Africa to the Americas and back again corresponded to the same cosmic forces that set the Atlantic currents in motion, and in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the merchants, manufacturers, planters, and royal officials of northwestern Europe followed these currents, building trade routes, colonies, and a new transatlantic economy. They organized workers from Europe, Africa, and the Americas to produce and transport bullion, furs, fish, tobacco, sugar, and manufactures. It was a labor of Herculean proportions, as they themselves repeatedly explained.

The classically educated architects of the Atlantic economy found in Hercules—the mythical hero of the ancients who achieved immortality by performing twelve labors—a symbol of power and order. For inspiration they looked to the Greeks, for whom Hercules was a unifier of the centralized territorial state, and to the Romans, for whom he signified vast imperial ambition. The labors of Hercules symbolized economic development: the clearing of land, the draining of swamps, and the development of agriculture, as well as the domestication of livestock, the establishment of commerce, and the introduction of technology. Rulers placed the image of Hercules on money and seals, in pictures, sculptures, and palaces, and on arches of triumph. Among English royalty, William III, George I, and George II’s brother, the “Butcher of Culloden,” all fancied themselves Hercules.1 John Adams, for his part, proposed in 1776 that “The Judgment of Hercules” be the seal for the new United States of America.2 The hero represented progress: Giambattista Vico, the philosopher of Naples, used Hercules to develop the stadial theory of history, while Francis Bacon, philosopher and politician, cited him to advance modern science and to suggest that capitalism was very nearly divine.

These same rulers found in the many-headed hydra an antithetical symbol of disorder and resistance, a powerful threat to the building of state, empire, and capitalism. The second labor of Hercules was the destruction of the venomous hydra of Lerna. The creature, born of Typhon (a tempest or hurricane) and Echidna (half woman, half snake), was one in a brood of monsters that included Cerberus, the three-headed dog, Chimera, the lion-headed goat with a snake’s tail, Geryon, the triple-bodied giant, and Sphinx, the woman with a lion’s body. When Hercules lopped off one of the hydra’s heads, two new ones grew in its place. With the help of his nephew Iolaus, he eventually killed the monster by cutting off a central head and cauterizing the stump with a flaming branch. He then dipped his arrows in the gall of the slain beast, which gave his projectiles fatal power and allowed him to complete his labors.

From the beginning of English colonial expansion in the early seventeenth century through the metropolitan industrialization of the early nineteenth, rulers referred to the Hercules-hydra myth to describe the difficulty of imposing order on increasingly global systems of labor. They variously designated dispossessed commoners, transported felons, indentured servants, religious radicals, pirates, urban laborers, soldiers, sailors, and African slaves as the numerous, ever-changing heads of the monster. But the heads, though originally brought into productive combination by their Herculean rulers, soon developed among themselves new forms of cooperation against those rulers, from mutinies and strikes to riots and insurrections and revolution. Like the commodities they produced, their experience circulated with the planetary currents around the Atlantic, often eastward, from American plantations, Irish commons, and deep-sea vessels back to the metropoles of Europe.

In 1751 J. J. Mauricius, an ex-governor of Suriname, returned to Holland, where he would write poetic memoirs recollecting his defeat at the hands of the Saramaka, a group of former slaves who had escaped the plantations and built maroon communities deep in the interior jungle, and who now defended their freedom against endless military expeditions designed to return them to slavery:

There you must fight blindly an invisible enemy

Who shoots you down like ducks in the swamps.

Even if an army of ten thousand men were gathered, with

The courage and strategy of Caesar and Eugene,

They’d find their work cut out for them, destroying a Hydra’s growth

Which even Alcides [Hercules] would try to avoid.

Writing to and for other Europeans assumed to be sympathetic with the project of conquest, Mauricius cast himself and other colonizers as Hercules, and the fugitive bondspeople who challenged slavery as the hydra.

Andrew Ure, the Oxford philosopher of manufactures, found the myth to be useful as he surveyed the struggles of industrial England in 1835. After a strike among spinners in Stayleybridge, Lancashire, he employed Hercules and his rescue of Prometheus, with his delivery of fire and technology to mankind, to argue for the implementation of the self-acting mule, a new machine “with the thought, feeling, and tact of the experienced workman.” This new “Herculean prodigy” had “strangled the Hydra of misrule”; it was a “creation destined to restore order among the industrious classes, and to confirm to Great Britain the empire of art.” Here again, Ure saw himself and other manufacturers as Hercules, and the industrial workers who challenged their authority as the hydra.

When the Puritan prelate Cotton Mather published his history of Christianity in America in 1702, he entitled his second chapter, on the antinomian controversy of 1638, “Hydra Decapita.” “The church of God had not long been in this wilderness, before the dragon cast forth several floods to devour it,” he wrote. The theological struggle of “works” against “grace” subverted “all peaceable order.” The controversy raised suspicions against religious and political officials, prevented an expedition against the Pequot Indians, confused the drawing of town lots, and made particular appeals to women. For Mather, the Puritan elders were Hercules, while the hydra consisted of the antinomians who questioned the authority of minister and magistrate, the expansion of empire, the definition of private property, and the subordination of women.

It would be a mistake to see the myth of Hercules and the hydra as merely an ornament of state, a classical trope in speeches, a decoration of ceremonial dress, or a mark of classical learning. Francis Bacon, for example, used it to lay the intellectual basis for the biological doctrine of monstrosity and for the justifications of murder, which themselves have a semantics of Latin euphemism—debellation, extirpation, trucidation, extermination, liquidation, annihilation, extinction. To cite the myth was not simply to employ a figure of speech or even a concept of analytic understanding; it was to impose a curse and a death sentence, as we will show.

If the hydra myth expressed the fear and justified the violence of the ruling classes, helping them to build a new order of conquest and expropriation, of gallows and executioners, of plantations, ships, and factories, it suggested something quite different to us as historians—namely, a hypothesis. The hydra became a means of exploring multiplicity, movement, and connection, the long waves and planetary currents of humanity. The multiplicity was indicated, as it were, in silhouette in the multitudes who gathered at the market, in the fields, on the piers and the ships, on the plantations, upon the battlefields. The power of numbers was expanded by movement, as the hydra journeyed and voyaged or was banished or dispersed in diaspora, carried by the winds and the waves beyond the boundaries of the nation-state. Sailors, pilots, felons, lovers, translators, musicians, mobile workers of all kinds made new and unexpected connections, which variously appeared to be accidental, contingent, transient, even miraculous.

Our book looks from below. We have attempted to recover some of the lost history of the multiethnic class that was essential to the rise of capitalism and the modern, global economy. The historic invisibility of many of the book’s subjects owes much to the repression originally visited upon them: the violence of the stake, the chopping block, the gallows, and the shackles of a ship’s dark hold. It also owes much to the violence of abstraction in the writing of history, the severity of history that has long been the captive of the nation-state, which remains in most studies the largely unquestioned framework of analysis. This is a book about connections that have, over the centuries, usually been denied, ignored, or simply not seen, but that nonetheless profoundly shaped the history of the world in which we all of us live and die.

Product details

- ASIN : B00BH0VRG8

- Publisher : Beacon Press (September 3, 2013)

- Publication date : September 3, 2013

- Language : English

- File size : 14.1 MB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Not Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Print length : 452 pages

- Best Sellers Rank: #693,697 in Kindle Store (See Top 100 in Kindle Store)

- #270 in Slavery & Emancipation History

- #314 in Social Classes & Economic Disparity

- #504 in Colonialism & Post-Colonialism

- Customer Reviews:

About the authors

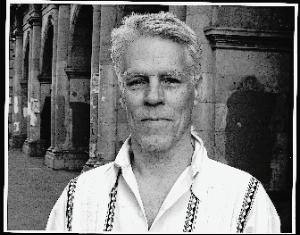

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read book recommendations and more.

Marcus Rediker is Distinguished Professor of Atlantic History at the University of Pittsburgh and Senior Research Fellow at the Collège d’études mondiales in Paris. He is the author of numerous prize-winning books, including *The Many-Headed Hydra* (with Peter Linebaugh), *The Slave Ship*, and *The Amistad Rebellion*. He produced the award-winning documentary film *Ghosts of Amistad* (Tony Buba, director), about the popular memory of the *Amistad* rebellion of 1839 in contemporary Sierra Leone.

Photo credit Curtis Reaves.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Learn more how customers reviews work on AmazonCustomers say

Customers find the book interesting to read, with one noting it is well-researched. The pacing receives positive feedback, with one customer highlighting how it breaks down major historical events and serves as an excellent introduction to social movements.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Select to learn more

Customers find the book interesting and well-written, with one customer noting its thorough research and helpful index.

"...within a discussion of the historical forces of the era, making the book an interesting, thought provoking and entertaining read...." Read more

"Excellent book on people that influenced the revolution from a non- traditional narrative...." Read more

"...in all, the shortcomings are few and the strengths many in this well-written book about the origns of our modern world...." Read more

"Very well researched, this is the history they dare not teach in schools, or re-enact on the history channel." Read more

Customers appreciate the pacing of the book, with one review noting how it breaks down major historical events and relates them to recurring themes, while another describes it as an excellent introduction to social movements.

"...Short narratives, biographies and illustrations of key events and individuals are framed within a discussion of the historical forces of the era,..." Read more

"...this story is complete with many "endnotes" and excellent illustrations covering all the periods they looked at...." Read more

"...It breaks things down to explain major historical events and how they relate back to one reoccurring theme...." Read more

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews. Please reload the page.

- Reviewed in the United States on August 28, 2004"The Many Headed Hydra" by Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker is an exceptionally well-written and enlightening history of early capitalism. The authors offer a bottom-up theory of resistance and describe the conditions by which the modern nation state was founded as a solution to the problem of proletariat self-rule. Short narratives, biographies and illustrations of key events and individuals are framed within a discussion of the historical forces of the era, making the book an interesting, thought provoking and entertaining read.

Linebaugh and Rediker describe the brutal process of primitive accumulation where the poor were forced off the land to create the proletariat class. The newly-dispossessed were disciplined harshly and made to labor for the benefit of the investor class. However, the pervasive "culture of fear" that was "indispensible to the creation of labor-power as a commodity" eventually led to revolt, first with the English Civil War in the 1640s and later throughout the colonial system.

The authors spotlight individuals who made the case for the rights of all people, including Edward Despard, James Naylor, Tom Paine, Thomas Spence and Robert Wedderburn. These voices articulated the desires of the masses to achieve equality and social justice. As these rights were consistently denied, the seeds of discontent and rebellion were planted. When not organizing resistance against empire, many chose piracy, formed their own renegade communities, or chose to live among the Native Americans.

In this light, the authors present the American Revolution as a cooptation of the democratic movement. Capitalist property and wage relations were legislated in a manner that secured elitist privilege. Race, sex and class effectively served to split the proletariat into factions that could be politically controlled. The nation state thus was born as an instrument to empower the bourgeoisie and channel the energies of the masses towards capitalist accumulation.

The unique value of this book is its convincing argument that the world we know may have turned out very differently. This tantalizing possibility is just one reason why "The Many-Headed Hydra" is an intriguing read. I highly recommend it to all.

- Reviewed in the United States on April 10, 2023Excellent book on people that influenced the revolution from a non- traditional narrative. The American Revolution was heavily influenced by sailors and motley crews.

- Reviewed in the United States on July 3, 2013It shows the inside out and ugly side of just how we came about. The use of slaver, where it became racialized (black, brown, red only eventually) how it was used. The philosophy of terror formulated by the likes of Sir Francis Bacon, to decapitate the hydra. What they called the multifarious groups against their enterprise of Capitalism (fledgling), empire, slavery and terror used to destroy the commons, separate and destroy those pockets and undercurrent of rebellion against all those notions promulgated by the powers including the Christian church and its concepts of dominion and slavery as being god given.

How Hercules, who slain the hydra was picked as an example of their hero, the one that cut off the heads of the hydra and burned the necks to stop regeneration. How they were metaphorical symbols of their work to remake the wild lands of the Americans and at the same time drain their lands of the people and ideas they found so disagreeable.

An excellent addition to any personal library on history and human rights and the foundations of imperial thinking still alive and well in places like the USA. Are you part of the Hydra or with Hercules?

- Reviewed in the United States on October 16, 2001The Many-Headed Hydra will appeal to readers interested in history "from the bottom up". Most histories look at the past from the viewpoint of kings, queens, priests, and others "at the top". In this book, instead of hearing from popes and potentates, we hear the voices of many speakers for and from the poor and forgotten, the working men and women of the English commons, the factories, the tall ships, and the plantations.

As the subtitle makes clear, this is mainly a history of sailors, slaves, and common people who are often ignored or downplayed in history books. The authors contend that these were the men and women mainly responsible for the rebellins and revolts and wars for independence fought in the Atlantic world from 1600 to 1800. In this book, the poeple who actually led the struggle, such as Crispus Attucks in the Boston Massacre, take center stage. The so-called leaders, from Cromwell to Jefferson, end up with supporting roles and sometimes even play the antagonists' part.

Although the authors write in a lively, engaging manner, some general readers may find the going tough at some points. Both of the authors are history professors, and they clearly feel strongly about what they've written. They don't use lots of specialized historical terms, but they do use many words specific to the periods they are considering. I think they could've helped a lot by including a glossary of some expressions hard to find without an unabridged dictionary. (There's only so much that one can guess from context.)

Also, general readers should approach this book as they would a good novel. For example, sometimes the authors mention people almost out of the blue, as if they'd already been introduced. In fact, they are participants from upcoming chapters. In short, some readers will need to give the authors a little leeway to tell their story, as we would in a novel.

Unlike a novel, this story is complete with many "endnotes" and excellent illustrations covering all the periods they looked at. The book also has a helpful index, but there's no one single list of books and articles. Readers who want to learn more about a particular person or topic will have to follow the trail of notes to the first time a work is cited.

Since this is a book about the Atlantic world, I was a little disappointed to find only one map, a map from 1699, and it's on the very last page before the notes (p. 354). I would've put it earlier, near the start, and I would've added a more modern map of the region for those readers not familiar with the old names.

All in all, the shortcomings are few and the strengths many in this well-written book about the origns of our modern world. (I haven't read as passionate and engaging a history since C.L.R. James's _The Black Jacobins_, Vantage Press, 1989.)

This kind of book may turn our world upside down, but it's about time we saw it from a different perspective.

- Reviewed in the United States on August 5, 2013This book is a great introduction to the history of social movements. It breaks things down to explain major historical events and how they relate back to one reoccurring theme. History surely repeats itself - what you learn from this book can be applied to the world today.

- Reviewed in the United States on September 28, 2017Very well researched, this is the history they dare not teach in schools, or re-enact on the history channel.

Top reviews from other countries

James SquiresReviewed in Canada on March 26, 2018

James SquiresReviewed in Canada on March 26, 20185.0 out of 5 stars Five Stars

Great Story !!

GerminalReviewed in the United Kingdom on July 20, 2015

GerminalReviewed in the United Kingdom on July 20, 20155.0 out of 5 stars Motley Crew

The title of the book is a reference to Hercules' heroic slaying of a monster in Greek mythology. As capitalism emerged in its early days, the emergent working class fought back against the effects of enclosures, enslavement and exploitation, and the chroniclers of early capitalism frequently referred to the many-headed hydra as a metaphor for this new monster that needed to be tamed.

The book is also about the conquest of the sea which established a new stage in human history and enabled the emergence of a globalising capitalism. Alongside this, however, there was a trans-Atlantic circulation of experience and struggle. Poorly paid, malnourished sailors were thrown together with slaves, transported criminals and conscripts in circumstances which created a common bond. So Linebaugh and Rediker trace a continuity of radical and revolutionary tradition that commences in the English Revolution with the Levellers, takes to the sea, continues and informs revolutionary, radical and democratic movements. A key feature of the book is the Motley Crew of the pirate ship a multi-coloured or indeed multi-ethnic group and such a motley crew was to be found on the ships that sailed the Atlantic stirring up a revolutionary current. Pirate revolts loom large - but not the stuff of Hollywood movies but the creation of radical democratic communities at sea. The book brings to life the multi-ethnic and internationalist nature of a whole series of struggles including the English Revolution, the Masaniello revolt in Naples in 1647, the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution and the anti-slavery movement in Britain.

It's a great book that brings obscure movements and individuals to life, rescues them from mainstream history and provides us today with some inspiring moments.

popeyethetimReviewed in the United Kingdom on October 3, 2016

popeyethetimReviewed in the United Kingdom on October 3, 20165.0 out of 5 stars Excellent history book which would go into my top five ...

Excellent history book which would go into my top five all time favourite history books

This springs from the gratitude to Christopher Hill and the analysis by generally Marxist historians of the English Revolution and particularly through and extending the work within 'The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution.

Linebaugh and Rediker follow a teasing and beautifully connected line from the outcasts of the English Revolution and its subsequent counter-revolution and follows the subsequent rise of revolution and the birth and growth of Capitalism. The essential parts of this are through the plantation system, slavery and the growth of the 'Motley Crew'.

They cite events and characters which have for the most part been lost to popular knowledge, and through this they elicit and characterise the essential changing nature and perception of history.

Gilly GReviewed in the United Kingdom on April 2, 2024

Gilly GReviewed in the United Kingdom on April 2, 20244.0 out of 5 stars Well worth the read

A very interesting read . I learnt a lot of new bits of history. That sent me down the Google search rabbit hole, which I love.

David BradshawReviewed in the United Kingdom on March 26, 2016

David BradshawReviewed in the United Kingdom on March 26, 20163.0 out of 5 stars Simultaneously a compelling and frustrating read.

This would be a fascinating and compelling read if it had received a severe but sympathetic editing. Having had my own work edited by others and vice-versa, I know this is painful but very necessary element of the publishing process. As the stands now, the text is overly wordy and complex.